An introduction, an ancient road, the journey through Emilia Romagna begins!

It all begins with an idea.

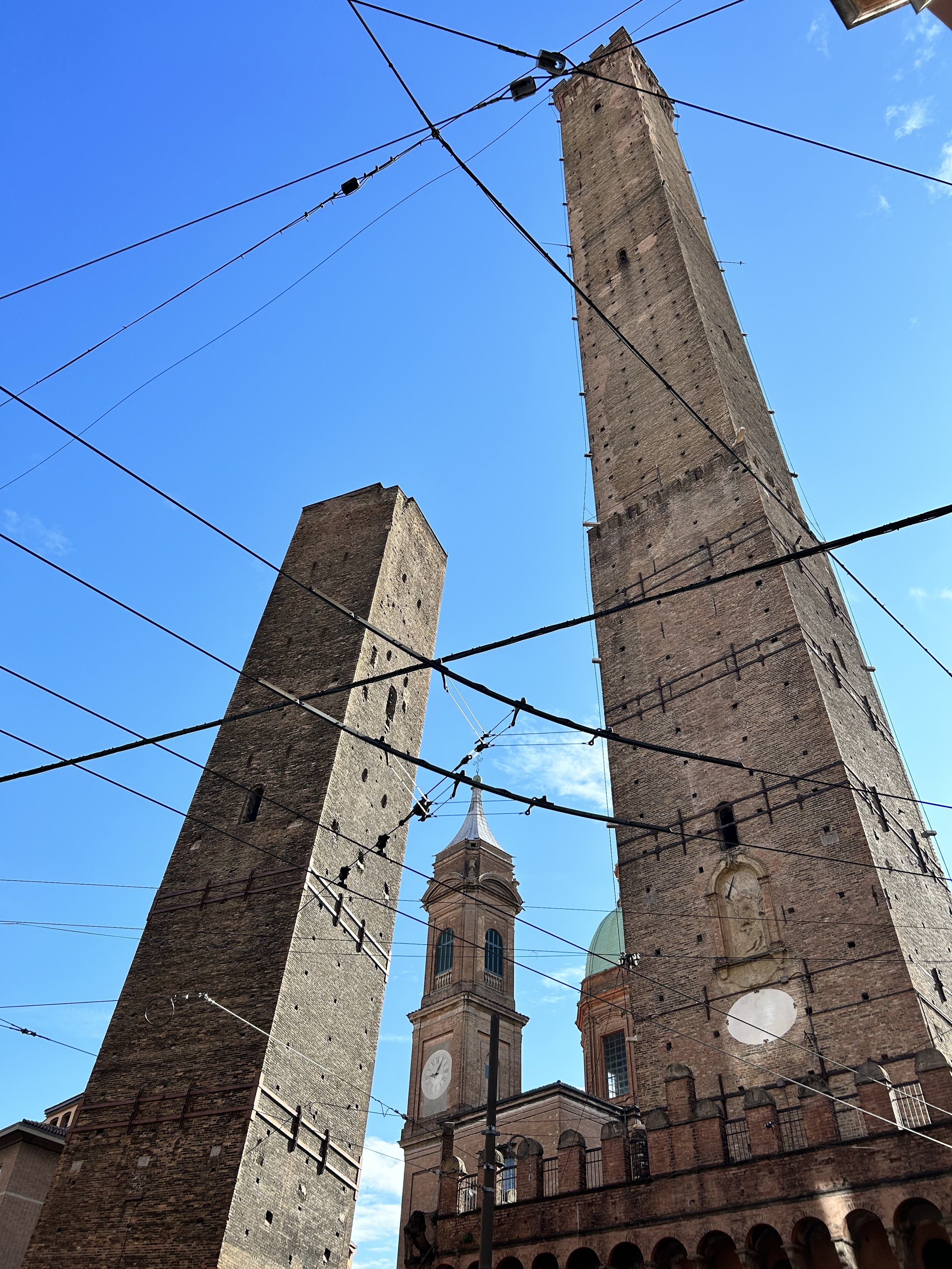

Due Torri-Bologna

Due Torri – Torre degli Asinelli e Garisenda: icons of Bologna, standing proudly where the ancient Via Emilia first entered the city.

The Via Emilia, carved by the Romans in 187 BC, stretches from Rimini on the Adriatic coast to Piacenza on the River Po. Built to connect and establish new colonies—Bologna (pictured), Modena, Reggio Emilia, and Parma—it remains the backbone of this extraordinary food and cultural corridor.

My goal here is simple: to share my journey—past, present, and future—through this rich, fertile land I’ve grown to know and love: Emilia-Romagna.

I was born in Australia, trained at culinary school in New York City, ran a successful salumeria in North Carolina, and now find myself fully immersed in Emilia-Romagna. Through this newsletter, I’ll bring you along: restaurant discoveries, honest reviews, local traditions, historical insights, travel stories, and, of course, the joys of Cucina Emiliana. 🐖

Writing isn’t new to me. Back in 2009, I ran a blog (dmanburger.wordpress.com) chronicling the quest for the best burger in one of the world’s great food cities, and even had pieces published on New York Magazines Grub Street, among others.Today, I’ve swapped burgers for salumi, prosciutto, gnocco fritto, tagliatelle al ragù, friggione, stracchino, and Parmigiano Reggiano Vacca Bianca Modenese from Caseificio Rosola.

Caseificio Rosola-Zocca, MO

Along the way, I’ve discovered the Terre di Castelli, the Lands of Castles: a stretch of terrain bridging the fertile plains of Emilia with the rolling hills of the Apennines, on the border of Modena and Bologna provinces. Comprising eight towns within the Unione di Castelli, each village offers its own cultural and gastronomic treasures—more stories to come, and I can’t wait to share them with you.

Iniziamo un viaggio!

—Darren

an experience in Valsamoggia, the star of Emilia Romagna-Michelin style!

a star in Savigno

a stage at Amerigo 1934 in Savigno

OCT 15, 2022

I was hurtling along the SP 26 in a midnight-blue Audi rental, carving through the Colli Bolognesi. Hairpin turns doubled back on themselves, steep ascents gave way to sudden descents, and everywhere, the vineyards of pignoletto glowed in the fading afternoon light. I was alive. Truly alive. In Valsamoggia.

Road to Savigno

Valsamoggia, a relatively new commune stitched together from a cluster of towns between Bologna and Modena, the hills roll like a living painting: emerald grass, sunburst-orange rooftops catching the last light, and an azure sky so vivid it almost hurts your eyes. This is the brilliance of Emilia-Romagna laid bare.

The food here is equally brilliant. Amerigo 1934, a small trattoria, bottega, and locanda tucked into Savigno—the town famous for white truffles each October—is a touchstone of the valley’s cuisine.

Morta Romagnola Salumi

I had dreamt of working here for years. I never imagined I’d get the chance to stage in a kitchen with Michelin-star pedigree. But ambition, and a little forwardness, can go a long way.

Tortellini

My first visit to Amerigo was back in 2021; I returned in 2022 for dinner. The restaurant sits at the end of the main street, where a mini piazza wraps around the town like a welcome mat. Inside, it’s quiet and intimate: antique wooden tables, rich curtains, white tiles, and an espresso bar that feels like a museum of historical collectibles. My friend from Bologna and I sat outside, awed by a three-page menu of seasonal, locally sourced ingredients. After some agonizing indecision, I settled on the summer tasting menu.

The meal began with upside-down cake studded with yellow tomatoes—sweet, delicate, with a subtle acidity that woke the palate. Potato gnocchi followed: soft pillows showered with scorzone black truffles, sourced just meters away. For the secondi, a leg of Apennine fallow deer smoked with cherry wood, accompanied by wild mushrooms, tubers, and local greens, emerged from the kitchen with quiet majesty. Dessert was deceptively simple: gelato drizzled with tradizionale balsamic. There was nothing flashy, nothing ostentatious—just food that moved you.

I knew then that I needed to learn from these people. Chef Alberto Bettini. I slid into his DMs on Instagram—a little audacious, but polite—and asked if I could stage in his kitchen. He said yes.

My first day began with the dolci: biscotti, crostate, gelati, and breads for the small cohort of hotel guests staying nearby. Claudia, my mentor, is a Bolognese force of nature: patient, meticulous, and pure gold at heart. The kitchen squad—Giacomo, Maria, Roberto (“Drago”), Alessio—and Roberta, the sfoglina, each brought their craft to life. Luca ran the front of house with quiet authority. By Wednesday, it was pasta day.

Tortelli con parmigiano reggiano

Roberta wielded her mattarello like a conductor’s baton, passing down a rhythm learned from her grandmother. Anna, a local with a laugh that could light up a room and a tongue sharper than a chef’s knife, kept the gossip and stories flowing. Together, we made tagliatelle, ravioli di friggione, tortelli ripieni di Parmigiano Reggiano with prosciutto di Mora Romagnola, gnocchi, and tortellini.

TORTELLI RIPIENI DI PARMIGIANO REGGIANO CON. PROSCIUTTO DI MORA COTTO NEL FORNO A LEGNA

Thursday was a symphony of prep: caprino, alchermes, Lambrusco gelato, tigelle, ragù, friggione, veal cheeks braised in Barolo, brodo for the tortellini, bacala, sfoglia lorda, and morels. The kitchen was a Zen state. No stress. No yelling. No ego clashes. Just execution, grace, and a love for food that’s palpable in every gesture. “Is this really a kitchen?” I asked myself. It felt more like a temple.

Tartufi

The kitchen was as organized and smooth running as anything I’ve ever seen. There was no stress, no arguments, no tension. Everything was executed with ease and passion. Service was flawless and quick, chefs were talking, everyone relaxed, no smack talk even! -“was this really a kitchen”? I asked myself, or some kind of zen get together of cooks. I loved every minute.

Caseificio Rosola

My day off, orchestrated by Chef Bettini, remains indelible. I toured Caseificio Rosola, the only producer of Vacca Bianca Modenese Parmigiano Reggiano in the hills of Zocca. I visited Ca’Lumaco, crafting Mora Romagnola prosciutto aged up to four years. And Corte d’Aibo, an agriturismo and organic winery tucked in the Regional Park of the Abbey of Monteveglio. These are the sources behind the magic at Amerigo.

Valsamoggia has me hooked. The hills, the food, the people—they’ve carved themselves into my memory. And I can’t wait for what comes next.

No! we don’t serve Spaghetti Bolognese here. This is Bologna-it’s ragù

“80 percent of Italian cooking is about getting the best ingredients the other 20 percent is about not fucking them up!” Evan Funke

JAN 07, 2023

What Is Italian Food, Really?

“No such thing as ‘ancient Italian cuisine,’” Alberto Grandi once declared, and yes, he’s ruffled more than a few aprons. Grandi, food historian and professor at the University of Parma, argues that much of what we call traditional Italian food is…modern. According to him, dishes like carbonara, panettone, and even some Parmigiano Reggiano are post-WWII inventions—or heavily reinvented. The idea of a unified “Italian cuisine” is largely a 20th-century construct, a way to forge a national identity. In his words, many culinary “traditions” are fairy tales.

It’s provocative, sure. But as I stare down a steaming bowl of Tagliatelle al ragù in Bologna, I don’t care whether it’s 50 years old or 500. Tradition here is measured not in decades, but in obsession.

Italian food is seasonal, local, and fiercely tied to place. What you eat in April isn’t what you eat in December. Easter is different from Christmas. Recipes vary by town, by grandmother, by family. And heaven help you if you argue about ragù in Bologna. I’ve witnessed debates—lively, aggressive, and just a touch combative—about the “correct” method. “Cosa fai con il ragù?!” someone exclaimed once, aghast at a less-than-orthodox approach.

And yes, let’s get it out of the way: spaghetti Bolognese does not exist here. At least, not as you imagine it. Italians roll their eyes when tourists ask for it. In Bologna, it’s ragù, and it belongs on tagliatelle. Thin, wide ribbons, not spaghetti. Sauce clinging perfectly to pasta, not drowning it like some overenthusiastic American adaptation. Opinions are like…well, you know.

Tagliatelle al ragù

The universal truth? Ask any Italian where to get the best Tagliatelle al ragù, and the answer is always the same: Mia mamma. Always.

Food here isn’t just sustenance—it’s identity, pride, and obsession. Everyone, rich or poor, considers where ingredients come from, who made them, and how they’re prepared. Even supermarket staples are leagues above what you’ll find in America. In Emilia-Romagna, a tiny osteria can serve Gramigna alla salsiccia, Tortelloni burro e salvia, or Passatelli for €7.50—and it will often outperform a pricier restaurant. Simplicity, executed flawlessly, is the region’s secret.

As an Australian-American chef living in Bologna, I chase these interpretations of classics. Tagliatelle al ragù is obsessive craftsmanship: fresh pasta rolled and folded by hand every day, boiled in salted water, tossed with a sauce rich with local meats, soffritto, wine, and passata, and finished with Parmigiano Reggiano. Each bite carries the story of hills, farms, kitchens, and the people who nurtured them—regardless of whether Grandi would call it a “modern invention.”

At Amerigo 1934, where I worked, Chef Alberto Bettini takes this devotion to a level bordering on reverent. The ragù is crafted from Vacca Bianca cows and Mora Romagnola pigs, with a soffritto, white wine, and passata. Roberta or Anna roll the pasta using flour ground at a 16th-century mill nearby. Tagliatelle hits the pan with just a touch of butter; Parmigiano is added at the very end. Rich, robust, irresistible. Every bite tastes of place, labor, and love.

Bologna is dotted with trattorie and osterie serving this dish. Grassilli, tucked down a cobblestone alley, delivers tiny salumi misti and ragù that sing. Trattoria da Me and Salsamentaria are comforting staples. Even in the tourist-heavy Quadrilatero, bowls for €9–€11 outperform more elaborate or expensive plates elsewhere.

Grandi might call it modern. But here, in kitchens, markets, and on the tables of mothers and restaurateurs, tradition is alive, spirited, and delicious. And just to be clear: no spaghetti. None. Tagliatelle only. Spaghetti Bolognese is a myth, a culinary chimera invented far from these hills.

So, if you’re here for the first time, relax. Take it all in. Surrender. To tagliatelle. To ragù. To obsession. And to the joy of eating like an Italian, whether it’s 50 years old or 500